The UK-based fabrication and welding company says that over a million new engineers and technicians will be needed by 2025 to sustain the fluid handling industry. According to a study by Engineering UK, there is a shortfall of 20,000 per year for people with level 4+ skills.

The lack of new talent in the engineering sector is persisting despite the Confederation of British Industry finding that 2017 manufacturing orders in the UK achieved a thirty-year high.

For Edgar Rayner, LTi’s lead and technical director, the issue has been compounded by Brexit, which could halt the supply of skilled workers from the EU. “We’re fortunate to employ some high calibre engineers in our team but hiring new people with the right skills or experience is by no means straightforward and, and I know we are not unusual here. Like many British engineering firms, we’ve also taken on skilled engineers from outside the UK, including our quality engineer who is eastern European. If we are to continue to grow our country’s manufacturing capability, we need to put skills development much higher up the national agenda.”

The British Pump Manufacturers Association in January emphasised the importance of a soft deal with the EU to retain essential personnel.

A report published by the Royal Academy of Engineering (RAE) in early 2017 outlines a number of causes for the skills deficit, including poor perceptions and understanding of engineering (something especially pronounced in the oil and gas sector) and the high cost of delivering an up-to-date engineering education. The Academy has been appointed by the government to lead the effort to improve diversity in the engineering sector and is looking to expand its school engagement programme to reach 1.1 million pupils from 70,000 over four years.

Attempts to improve engineering intake have seen some success, but by the Academy’s assessment it will not be enough to meet the projected shortfall.

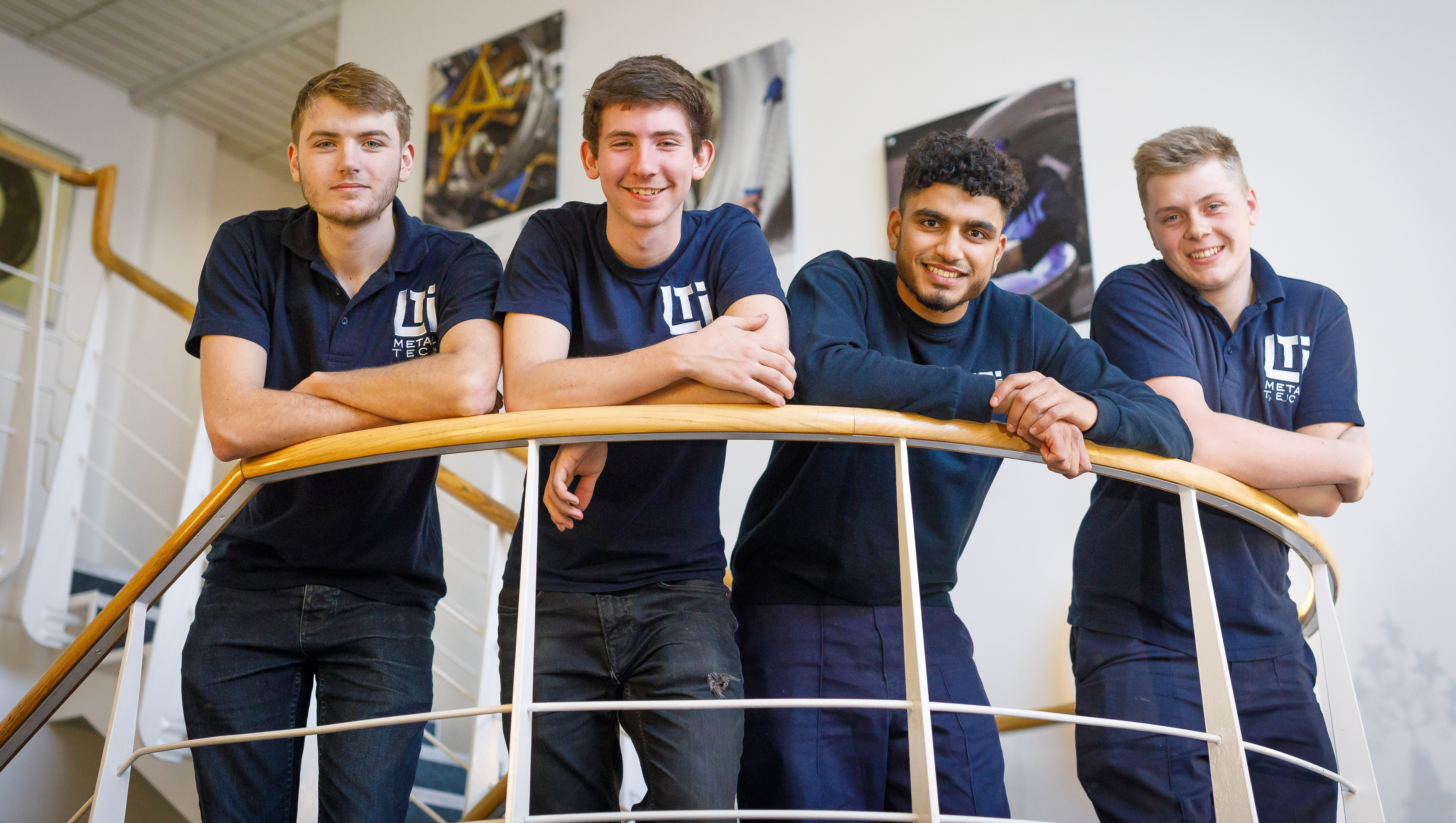

LTi sees apprenticeships as the primary means to address the problem, but engineering apprenticeships have often been criticized as chronically over-subscribed. Across the sector efforts are being made to increase the number of apprenticeships available and the forms they take, with schemes like Degree Apprenticeships letting students learn at an academic institution while also receiving practical training.

“From schools, universities and engineering companies to trade groups, associations, regulatory bodies and investors – all have a part to play. Only then will we create the environment needed to help bridge the skills gap,” said Rayner in a statement.

The government’s ‘Apprenticeship Levy’, a vehicle to fund more vocational programmes, took effect in April 2017. The stated goal is to increase the number of apprenticeships to 3 million by 2020. The levy takes the form of a 0.5% tax on annual employer pay bills over £3 million. According to the government, the levy will only affect 2% of employers.

There has been concern that the rapid growth in vocational schemes may lead to poorer programmes. The government responded by creating the Institute for Apprenticeships, a move meant to simplify and consolidate its efforts to promote vocational education.

CEO of the Institute Sir Gerry Berragan outlined the goal of the body in a 27 February speech on its progress so far: “to transform the skills landscape, fill the skills shortages, provide transformational opportunities for people seeking to up skill themselves and, ultimately, improve the productivity of this country”.